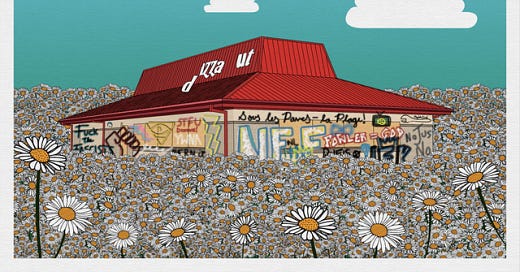

Abandoned Strip Mall Food Dreams

The Talking Heads and regenerative urban planning have a lot in common.

Welcome back to The Link, a bi-weekly circularity newsletter making the connection between regenerative farming and you, every other Tuesday.

Lately, I can’t stop listening to “Nothing but Flowers” by the Talking Heads.

Sometimes I blast it from my back porch, eating juicy slices of fresh summer watermelon in the twilight, watching the fireflies and dreaming about the future. It echoes in my head when I’m kneeling down in the soil of my sanctuary, planting flowers, seed by seed in my garden, imagining their little germination bodies writhing in harmonious, rhythmic joy to the instrumental chorus:

“There was a shopping mall/Now it's all covered with flowers/You've got it, you've got it.”

Throughout the song, David Byrne sings us through a post-apocalyptic world where modern technology has largely been eliminated. And as it goes on, Byrne’s world is torn between his appreciation for nature's beauty and his codependency on disappeared items of comfort like fast food and lawnmowers.

“With a beautiful highway/This used to be real estate/now it's only fields and trees/Where, where is the town/Now, it's nothing but flowers.”

It’s joyful, psychotic, and the perfect summer jam. It’s my tonic to all of this AI talk of late and the Bermuda Triangle-like conversations I often find myself in the climate community about how technology has the potential to save us all. Maybe it will, but what happens when we’re all wiped out? Nature will most definitely roll on all of us, including AI.

If you’re in a big city right now reading this and listening to the song as we speak, are you outside? If it’s a yes for you, what block are you standing on? What sorts of plants are busting through the cracks of hot pavement? Have you passed an abandoned strip mall? What does the biome you’re living in smell, look, and feel like at this very second?

I ask because there’s someone who’s blending the Talking Heads post-apocalyptic fever dream with a harmonious, tangible nature positive future. Regenerative landscape designer, Ali Mills, recently sat down with me to discuss the parallel issues plaguing big agriculture and modern horticulture design, why treating tiny hellstrips on your block as ecosystems is pretty impactful as an individual, and how deepening your connection to nature in cities as a radical, communal act.

First off, how does a fancy New Orleans bartender end up becoming a regenerative landscape designer?

I was managing cocktail bars in New Orleans for years, where I didn’t get out of work until 7 am. The natural rhythms and cycles of things were getting away from me. I was part of a system that was disconnected from where food comes from and the natural world in general. It took me a while to identify what it was but when I did, I looked around to try to find spaces that I could invest my time in and feel that connection to nature.

Everyone wants the pill that “cures you” in our society and not necessarily always connecting things to what you’re literally eating. Eating is the most intimate thing you do with the outside world every day. You’re taking the outside world literally into your body, and not considering the feedback loop of eating, which is so long. So it made me start thinking about nutrition and what we’re eating that’s impacting our mental and emotional lives.

I got into studying community nutrition, went back to school, and found that nutritionists and dietitians are dictated by government rules which are dictated by capitalism and lobbyists. Then I decided to move to Vermont, one of the more progressive farming states with food access and food distribution in the country, to attend a program at UVM that specialized in sustainable agriculture. I started to take residential garden clients on the side, which opened my eyes to the fact that the agriculture system is part and parcel to the general horticultural system and people are not really thinking about how what we plant in our physical environment affects us and the community as a whole. I ended up designing functional gardens for my clients: not just as a food source, but also fitting within the system in which they exist. Now I design gardens for clients who want to have a direct impact on the patches of land that they’re on. We hold ourselves so separate from nature in suburbia. The US tends to make nature something we’re supposed to go visit like a National Park instead of your own backyard or on your sidewalk hellstrip. I think that’s a shame and we should change it.

So what does it look like to employ mindful ecological stewardship in urban landscape design?

I think there’s this idea that the built landscape is separate from nature, but it’s not. We’ve gotten to a place where we’re both plant and ecosystem blind. Not too many people can walk outside their door and identify the weed growing next to their apartment but the hellstrip is part of nature and our cities are part of nature, and so to reframe our built environment as working with and in nature shifts your perspective to think about how to make different choices of what we place into the built environment. We do need to be responsive to the functionality of the ecosystems that we’re in. Some cities like Singapore are doing a great job of that and integrating climate resiliency into their landscape design.

The really easy thing to do is not grow a lawn if you have the opportunity. Our choices have cascading effects to the creatures that we coexist with: providing nectar and pollen support to the creatures that are here, rainscaping and storm filtration and all of these things that benefit our lives on a whole but on an individual level may not seem that important. If we could reimagine that paradigm and acknowledge its all part of one system, it would radically shift the way that we live in cities.

OK so dream scenario: You have access to an abandoned strip mall. What do you do with it?

The first thing that got me into botany and agriculture was food security and food access. There’s something to be said for the collaborative model. Make it into a community garden where people can come together and grow food for themselves. Maybe the roof is a garden and the inside is full of classrooms and greenhouses where people can learn how to grow food at different scales and more about things that are functional in their local biome. The results would help cast knowledge out to the community as a whole.

What are some other ways can people deepen their connection to nature in cities?

Look for opportunities to be awed by the natural world. If you have access to and can support more local foods, we need to find ways to make those systems more resilient. Even if it’s just watching something grow is really empowering and knowing that you’re a part of these fragile landscapes that we’ve built and imagining a reframe of what they can be, and knowing that life is always trying to break through the concrete.

I think people in cities of certain demographics have the responsibility to vote with their dollars for localized food access distribution. We won’t be able to get rid of large industrial farms because we have too many people to feed, but once you start to think about where your food comes from, the labor that goes into it, and how it’s grown is really important. It doesn’t take up a lot of space to get into it. You can even grow things in pots on your fire escape. Look at the in-between spaces between buildings—especially the “abandoned” areas as possibilities for functional growing.

How can people find your work?

You can find me/message me on Instagram, Aliofblooms. I am currently designing a bunch of mail order plant packs for home gardens that are designed to be functional in an ecosystem. The first one I did was a firefly habitat garden that includes a bunch of native plants, along with information on what people can do in their yards.

Thanks so much for speaking with me!

Oh hey! You’re still reading this? If you have future topics, smart humans, or concepts you’d like to see featured, respond to this newsletter or drop me a line and say hey: Helen@HelenHollyman.com.