A Murder of Crows on the Farm...

Mischief, root vegetable talismans, and a walk into the spirit realm on Hallows Eve

Welcome back to The Link, a bi-weekly circularity newsletter making the connection between regenerative farming and you, every other Tuesday.

Did you pause that episode of Ancient Aliens about portals last night to run up to Party City right before they closed to try to find the Halloween costume you’re in dire need of? OK I guess it’s just me, and no, no weed was involved. I’m not here to muse on one of my superpowers, procrastination, but instead ponder again about modern farming with you. You’ve probably heard something around the loose origins between Halloween and Samhain, which many people like to call “that witch holiday.” You (might) know the one: between the eve of October 31st and November 1st, the ancient Gaelic pagan festival marks the end of the harvest season, ushering in the start of winter and the Celtic new year. It’s also the Irish language name for November, and a sacred time that ancient Celts believed to be when the realm between life and death was the thinnest. On this night, Samhain, spirits could freely roam between the two worlds.

Its Gaelic origins involved large gatherings and feasts, when the ancient burial mounds were opened in order to enter portals to make contact with the “aos sí” or spirit world. According to certain sources, cattle were brought down from summer pastures and slaughtered and special bonfires were lit to provide protective and cleansing powers. Rituals during the festival included food and drink offerings to the spirit world to ensure that both humans and livestock survived through the winter.

Ancient Celts both welcomed and dreaded this holiday, fearing that they might cross paths with monsters, ancestral spirits, and fairies. So in order to protect themselves from creepy dead relatives and and ill-intentioned energies, they carved turnips, and in some cases potatoes and beets into jack-o’-lanterns (nicknamed after “Stingy Jack”—a spirit who “tricked the devil for his own monetary gain,”) to ward off bad vibes. Sound familiar?

These days, we are used to the pumpkin version of these bad boys (except for me, who is WILDLY ALLERGIC TO ALL PUMPKINS, no joke). If only we still embraced the root vegetable versions of this holiday, I wouldn’t break out in literal hives, but my vote doesn’t count in this season because “it’s decorative gourd season, motherfuckers.”

All this talk of root vegetables and livestock and the end of the harvest season and the spirit world brings me back to the energy of farms and the farmers who steward them. And naturally, my mind drifts off to the crows— the wildly intelligent bird who gets an understandably bad rap among farmers. Much like a drunk David Hasselhoff, crows will devour farmers’ recently planted seedlings, fruits, and corn, destroying their hard-earned efforts long before they sprout. And the crow’s corvid cousin, the raven (a much larger bird), often feasts on newly born, or recently hatched livestock and poultry (which can sometimes be via carrion). Don’t google the images—you can just rewatch The Birds from Hitchcock to get the gist (spoiler: they love eyeballs).

White-settler colonists in the United States and literal Europeans have serious hangups with crows. European folklore and modern fiction (I’m looking at you, Edgar Allen Poe), associates the species with trickery and death. And if you don’t agree with me, explain to me why the English word for a group of crows is a “murder.” Ever since the 1500s, if you want to throw serious shade at someone in England, all you have to do is tell them to “eat crow,” an idiom that suggests an unsavory move since they’ve been known to consume carrion. One particular self-proclaimed American “crow hater,” Dr. T. W. Stallings tried to nearly eradicate them in Tulsa, Oklahoma in the mid 1930s because they were destroying staple crops the community depended upon. Fair enough. Dr. Stallings pulled a sadistically foodie influencer move, transforming his hatred for them into a culinary delicacy, igniting a food trend of crow on every restaurant menu, hospital, and “crow banquet” in Tulsa. However, Dr. Stalling’s dream to eradicate the species was wildly unsuccessful, and this was longggg before TikTok existed.

Crows and ravens are some of the smartest animals in the world, on par with the intelligence of chimpanzees. They construct their own tools, hold grudges against humans and other animals, and host wakes and funerals for their dead. They even gossip. Like humans, they form close family units of up to five living generations. Yearlings and two-year-olds help their parents with chick-rearing, aiding in nest building, keeping it clean, and even feeding their mom while she’s sitting on the nest, because goddamn, women are world builders.

The bad news for farmers is that American crows have gotten even better at adapting into the Anthropocene than we have, especially in urban centers. With over 27 million of them in the US alone, their population has grown nearly 20 percent over the past 40 years. And as harrowing climate disasters like the recent hurricane in Mexico has signaled, we have a lot to learn about our own adaptation as we shift gears in the Anthropocene.

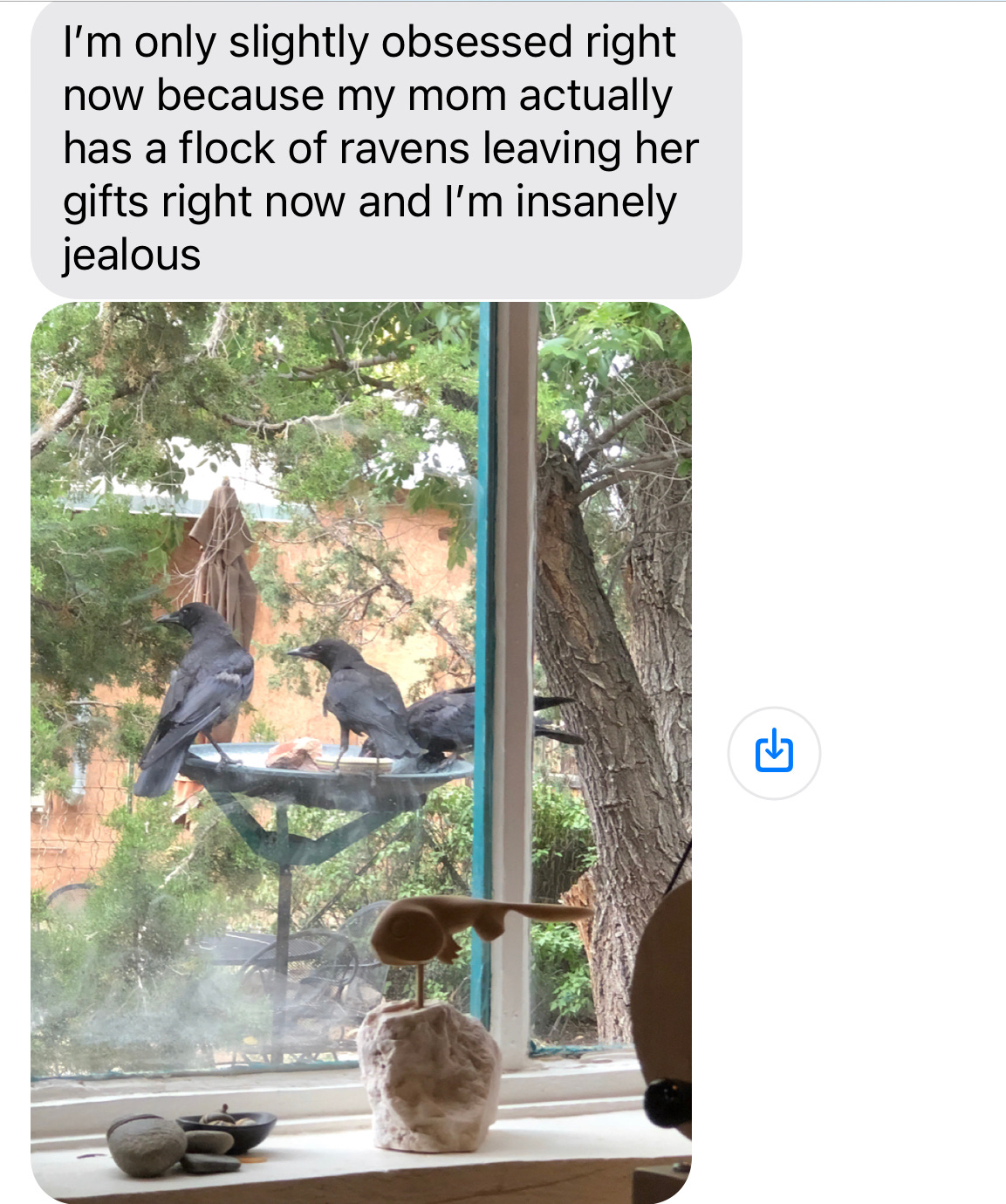

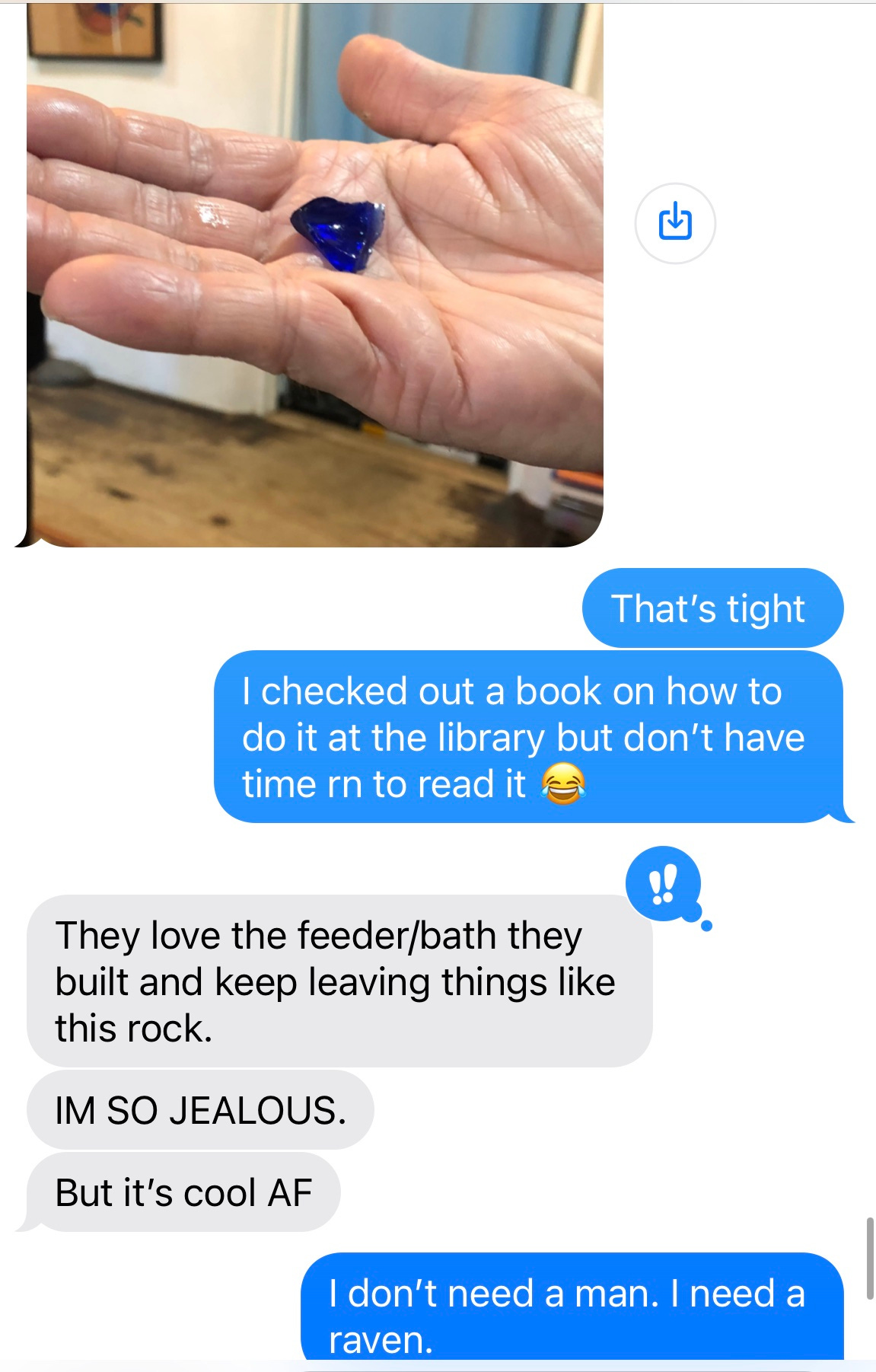

Some people have embraced the wisdom of crows and ravens, leaving them gifts in exchange for gifts. Just asked my best friend Ali, who’s mom has a booming social life in Santa Fe that stems beyond her human pals. Her mom has been leaving ravens different snacks, and in return, they provide her with shiny, beautiful objects like pieces of glass. When I learned about it, it made me question my efforts on dating apps altogether.

One wise Reddit user claimed to leave them breadcrumbs, only to receive an ongoing payment of money and an impending moral crisis. (In all honesty who knows if this story is real but if it isn’t, I don’t want to know).

But to ground us back into the earth for a second, is there a crow upside for farmers? I can’t answer that question, and instead offer a mediation on Hallows Eve. Much like a lot of the pagan traditions that were vilified by the domination of Christianity (that’s an entirely other substack post), crows have taken on a sinister symbol in Western dominant culture. But crows are often associated with the spirit realm—serving as messengers from ancestors and spirits on the other side. They signal transformation and hold space for mystery and protection.

Hell, if you just remember to not treat them like an asshole, they won’t hold a grudge against you and become your friend. If you lock eyes with one (they’ll literally give you the side eye, which means they’re looking straight at you), just remember that they’re descendants of theropods, a.k.a. dinosaurs and have been here much longer than us. The next time you’re walking on a cement sidewalk and see or hear one, look up and thank them for their wisdom, mischief, and brilliance. It might not be immediately revealed to you, but as we head into the darkness of winter, their shadow work has the potential to bring you closer to epiphanies, large and small.

Happy Halloween!

Oh hey! You’re still reading this? If you have future topics, smart humans, or concepts you’d like to see featured, respond to this newsletter or drop me a line and say hey: Helen@HelenHollyman.com.

And if you liked this post from The Link, I dare you to share it!